Letko Brosseau

Veuillez sélectionner votre région et votre langue pour continuer :

Please select your region and language to continue:

We use cookies

Respecting your privacy is important to us. We use cookies to personalize our content and your digital experience. Their use is also useful to us for statistical and marketing purposes. Some cookies are collected with your consent. If you would like to know more about cookies, how to prevent their installation and change your browser settings, click here.

Pension System

Frequently Asked Questions

October 2023

The Pension System

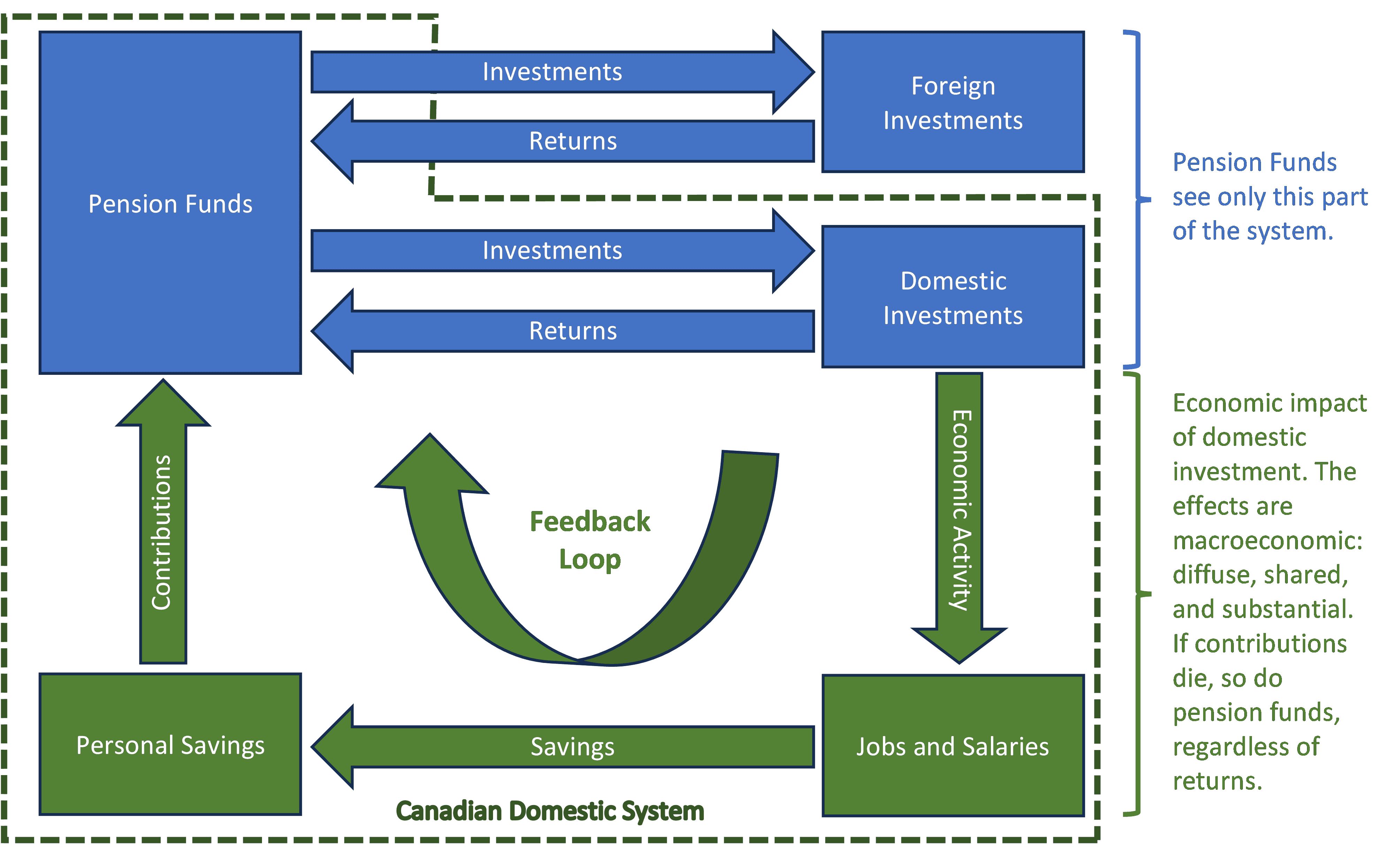

The BLUE represents the world as viewed by pension investment managers. They see a world of investment opportunities, each presenting a certain risk and offering a return potential. Whether the investment is foreign or domestic makes little difference from their perspective.

The GREEN represents the domestic economic system illustrating that domestic investments create domestic jobs which pay salaries, generate savings, and allow contributions into the pension funds. Without this GREEN cycle, there would be no jobs, no salaries, no savings, no contributions, and no pension funds. These are macroeconomic effects which cannot be credited to individual pension funds or investments. The GREEN cycle is not part of pension managers’ perspective.

A simple example

CASE 1. A Canadian invests $100 abroad. After one year, they repatriate the $100 and $10 of profit. Their return is 10%.

CASE 2. A Canadian invests $100 in a machine that produces $205 of product in the year. The costs are $100 of salaries and $100 of wear on the machine, leaving $5 of profit. Their return is 5%.

In CASE 1 Canada’s GDP rises by $10, the profit. In CASE 2, GDP in Canada increases by $205, the salaries, the machine, and the profit.

From the Canadian investor’s point of view, the foreign investment gives a higher return but from a GDP perspective, from a GDP per capita perspective, from the perspective of Canada’s ability to save, the domestic investment is by far the better one.

Pension Funds Are Leaving Canada, but They Are Not to Blame

Pension funds’ reduced allocation to Canadian investments over the last 30 years is well documented[1].

Is the behaviour of pension fund managers contrary to sound financial principles?

No, they are comparing investments using well established financial principles of expected returns, risks, and diversification. One may disagree with some of their investment choices but not really with their methodology. We may think they should be more sensitive to the source of their funds, but sensitivity is not a financial requirement. The impact on the incomes of Canadians and on their ability to contribute to their pensions clearly differs between foreign and domestic investments. These differences are macroeconomic. They are not conducive to a classical portfolio risk and return analysis.

What are some commonly stated justifications for their behaviour?

- Higher expected foreign returns – not supported by history nor by forward looking valuation metrics.

- Diversification – a portfolio does not require reducing Canada to a 3% weight to diversify portfolio risk. It is possible to create a portfolio of 2/3 Canada and 1/3 US which equally weights all 11 market industries[2].

- Indexing – Canada is 3% of the MSCI and consultants often recommend this index weight. But this form of indexing means that the smaller a country, the less it should invest in itself. Maybe a better criterion would be to invest 75% in Canada, just like the US does.

- Lack of capacity – The equity market is 39% of household savings in Canada, while it is 37% in the US[3]. Canada’s capacity to absorb savings is comparable to the US. Furthermore, capacity is not fixed, it depends on the effort directed towards fostering it.

What is the problem and why is it not visible to pension funds?

Pension funds receive their contributors’ savings and are tasked with investing them. Their role in maintaining and increasing their members’ incomes and savings is indirect and diffuse.

Can pension funds consider system effects they cannot directly measure?

Pension funds can not measure the shared macroeconomic system impact their investments have on the domestic economy and thus, the impact is not part of the decision-making process. As Peter Drucker wrote, “You can’t manage what you can’t measure.[4]”

Are there other macroeconomic effects that cannot be appreciated at the portfolio level?

- Yes – Extensive indexing is bad for the economy because it means investors are not evaluating the specific merits of individual investments, an essential requirement for proper capital allocation within the economy.

- Yes – Private placements have their place but if illiquid, opaque, and subjective investments represent too great a percentage of overall portfolios then there is a system risk. An argument often made is that private markets suffer from inefficiencies and present greater return opportunities. This could lead to the perverse conclusion that managers prefer markets remain inefficient. Public markets compel disclosure and have more eyes-on which leads to better valuations and resource allocation in the economy.

Only Government Regulations Can Deal with The Problem

Does the government have a right to intervene?

As explained above, the level of domestic investment affects overall system costs and risks. Only the government can take these macroeconomic effects into account. As pension funds are highly tax assisted government creations, governments have every right to regulate them. They even have an economic imperative to do so.

Can moral suasion work?

Probably not because you cannot ask a pension fund to consider what it cannot measure. You can tell them it is bad if they do not invest in the domestic economy but how can they judge how bad?

Can dual mandates work?

Probably not for the same reasons as moral suasion, you cannot ask a pension fund to consider what it cannot measure, and even if it could, it would be difficult for it to judge how adequately it was fulfilling its two mandates. What would be insufficient? What would be enough?

What is the correct level of domestic investment?

Currently the only number out there is Canada’s 3% weight in the MSCI. What pension funds need is another number, in Australia, the number is conservatively 50%, and 75% in the US[5]. The government needs to set the number.

Should the level be unbreachable?

Many years ago, pension funds could only invest 10% of their assets outside of Canada[6]. It was a hard stop. A system of reserves could impose soft stops. If a pension fund decided to invest more than a stipulated portion of their assets outside of Canada, they would be required to set aside a reserve. This would create a disincentive but not an obligation. (See reserves below)

What are the advantages of reserves?

- They create incentives and disincentives,

- There is no hard stop. Reserves can be applied to condition multiple behaviours which impact the overall system: domestic investment, private equities, derivatives, indexed funds, etc.

Capacity

Are Canadian markets too small?[7]

In many respects Canadian markets are comparable to US markets, adjusting for the size of the economy and savings. Public equity markets are 39% of household savings in Canada while they are 37% in the United States. They account for 123% of GDP in Canada, less than the 164% in the US but comparable to the 127% in Japan, and greater than the 91% in the United Kingdom. The security with the largest market capitalisation in Canada is 6% of GDP while it is 12% in the US. The largest 100 companies total 104% of GDP in Canada and 113% in the US.

Non-residential capital investment in Canada in 2021 was approximately 10% or GDP while it was 13% in the US, 30% more. If we further adjust for the lower GDP per capita in Canada, the US invested 75% more per capita than Canada did. This means that there is ample room and need for additional investment in Canada. If the US can do it, so can we.

Are Canadian institutions too big?

Here lies the big difference between Canada and the US. The largest fund in Canada represents 20% of GDP and only 3% of GDP in the US. The top 10 funds represent 79% of GDP in Canada and only 12% of US GDP[8].

Can being big limit investment?

If the largest fund in the US was to invest all its funds in US equities, their average holding in each company would be 3% / 164% = 2% while in Canada it would be 20% / 123% = 16%, 8 times larger. Taking the top 10 funds together, their combined holdings would be 79% / 123% = 64% of the average company compared with 12% / 164% = 7% in the US. Funds wanting to limit their holdings in a company for liquidity reasons would hold back their investment[9].

What is the problem then: too small or too big?

It is common to hear large pension funds in Canada state that Canada is too small. The problem is not that the Canadian market is too small relative to the size of its economy, it is that the funds are close to 7 times larger and more concentrated in Canada than in the US. The regrouping of funds into larger units in Canada has exacerbated this problem. There is little to be gained by having such large funds in Canada but there is much to be gained by investing Canadian savings in the Canadian economy. We might have to choose between the two, but we should give pension funds a chance to invest more in the Canadian economy before concluding they cannot.

Reserves

How are plans valued?

Plans are valued based on their expected future pension liabilities and their assets. Netting one against the other establishes the plan’s surplus or deficit. Liabilities are calculated differently depending on whether the valuation is done for solvency or going concern purposes as is the rate used to discount future pension payments. Assets mostly remain the same regardless of the valuation purpose.

What could a reserve system look like?

Pension funds would be required to put aside reserves for certain asset classes and these reserves would not count when tabulating the plan’s assets for valuation purposes. The reserve system would not affect a plan’s liabilities.

What is an example of reserves?

Assume $100 is available for investment. If invested in a Canadian bank, no reserve would be required such that the full $100 could be invested in the bank and included in the plan assets. When invested in an Indonesian bank, a 20% reserve would be required. Only $80 could then be invested in the Indonesian bank and included in the calculation of the plan surplus or deficit, the remaining $20 being in a reserve.

Where could the reserves be invested?

There are many options here, but a simple solution would be to invest them in government treasury bills.

What would require reserves?

Reserves could be used to promote or discourage certain behaviours that have macroeconomic impacts. Examples of assets that might require reserves would be foreign investments, private placements, indexed funds, derivatives, and leveraged assets. The reserve requirements could vary by asset class or type. They could also start to apply only after a certain threshold is exceeded. For example, reserves would be required if foreign investments exceed 25%. Asset classes could also be grouped as some were under former legislation. For example, a basket of unapproved asset classes exceeding 10% of the plan could require a 30% reserve.

Who would own the reserves?

The reserves would belong to the plan and could be freed up by changing asset allocations.

What are some of the advantages of a reserve system?

- No hard stop. If a plan feels strongly about the prospects of an investment that would require a reserve, then they are always free to make the investment while providing for the reserve.

- Reserves could apply to many different asset classes.

- The level of reserves could vary depending on the type of asset.

[1] https://www.lba.ca/invest-in-canada/

[2] Achieved by taking each industry’s full weight of Canadian Index up to 9.1% and completing any missing portion with US index. The resulting portfolio is weighted approximately 2/3 Canada and 1/3 US.

[3] Statistics Canada and Federal Reserve

[4] https://www.contractguardian.com/blog/2018/you-cant-manage-what-you-cant-measure.html#:~:text=Peter%20Drucker%20is%20often%20quoted,improving%20and%20what%20is%20not.

[5] Willis Towers Watson, Think Ahead Institute and secondary sources.

[6] Income Tax Act, Canada 1991. Further see Bank of Canada Review Winter 1995-1996, p 37

[7] All statistics from Statistics Canada, Federal Reserve, and other governmental statistic offices.

[8] Statistics Canada, Fund annual reports.

[9] Fund annual reports, Statistics Canada.

Concerned about your portfolio?

Subscribe to Letko Brosseau’s newsletter and other publications:

Functional|Fonctionnel Always active

Preferences

Statistics|Statistiques

Marketing|Marketing

|Nous utilisons des témoins de connexion (cookies) pour personnaliser nos contenus et votre expérience numérique. Leur usage nous est aussi utile à des fins de statistiques et de marketing. Cliquez sur les différentes catégories de cookies pour obtenir plus de détails sur chacune d’elles ou cliquez ici pour voir la liste complète.

Functional|Fonctionnel Always active

Preferences

Statistics|Statistiques

Marketing|Marketing

Start a conversation with one of our Directors, Investment Services, a Letko Brosseau Partner who is experienced at working with high net worth private clients.

Asset Alocation English

Canada - FR

Canada - FR U.S. - EN

U.S. - EN