Letko Brosseau

Veuillez sélectionner votre région et votre langue pour continuer :

Please select your region and language to continue:

We use cookies

Respecting your privacy is important to us. We use cookies to personalize our content and your digital experience. Their use is also useful to us for statistical and marketing purposes. Some cookies are collected with your consent. If you would like to know more about cookies, how to prevent their installation and change your browser settings, click here.

Horizon

2021 FEDERAL BUDGETApril, 2021

Introduction

On April 19, the federal government tabled its first budget in more than two years. The budget confirms a deficit for the past year, which reflects the current situation. Several support measures for businesses and workers are extended and reinforced to put an end to COVID-19 and promote economic recovery. Minister of Finance Chrystia Freeland anticipates further deficits as the country emerges from the pandemic.

This newsletter summarizes the highlights of the budget, which contains more than 200 new measures. The summary is followed by our analysis. Since the budget has not yet been adopted by Parliament, the proposed measures could undergo changes.

Budgetary information

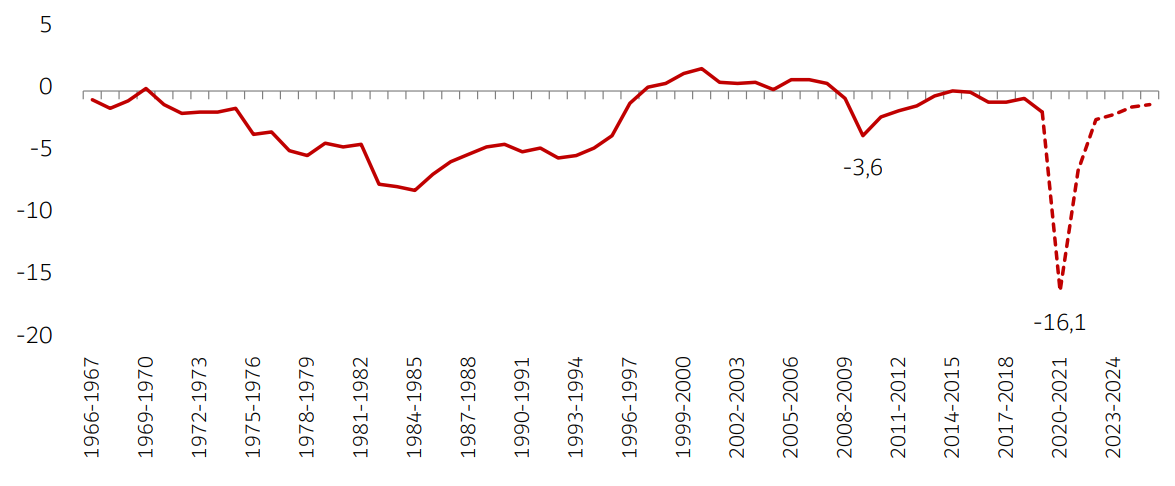

Unsurprisingly, the pandemic has caused a drop in revenues and an increase in federal government spending, resulting in a deficit of $354 bn or 16% of GDP for 2020-2021. In terms of percentage of GDP, this deficit is the highest since World War II; from 1942 to 1945, Canada’s deficit ranged from 17% to 22%.

Budgetary balance (% of GDP)

The federal government is also anticipating deficits in subsequent years. These are expected to decline gradually from $155 bn (6.4% of GDP) in 2021-2022 to $31 bn in 2025-2026. No target has been set for a return to balanced budgets.

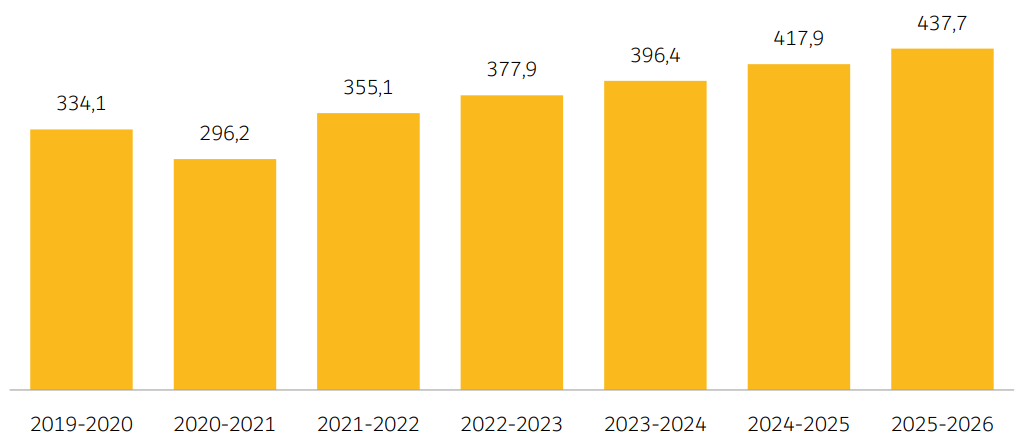

As for revenues, they declined in 2020-2021 (-11.3%) but are expected to exceed 2019-2020 levels in 2021-2022. Starting in 2022-2023, the average annual increase in revenues is projected to be 5.4%.

Budgetary revenues (billions of dollars)

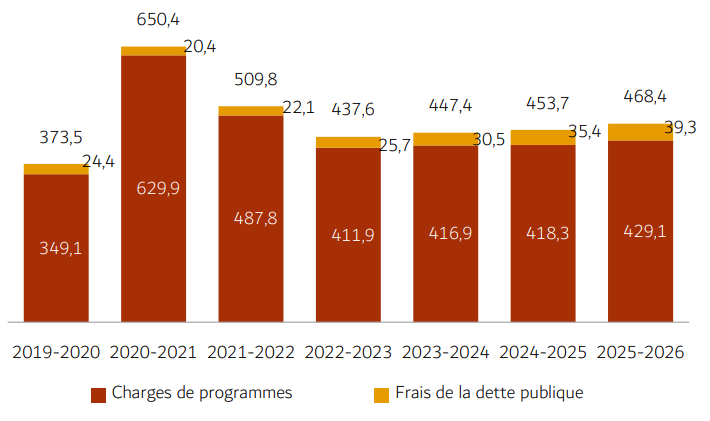

Expenditures will increase as part of an economic recovery program totalling $100 bn over a three-year period, broken down as follows: $49 bn in 2021-2022, $28 bn in 2022-2023 and $24 bn in 2023-2024.

Despite an increase in the debt, debt servicing costs will be lower in 2020-2021 and 2021-2022 than they were in 2019-2020. However, these costs represent an increasingly large proportion of revenues, and should exceed pre-pandemic levels as of 2023-2024.

Expenditures (billions of dollars)

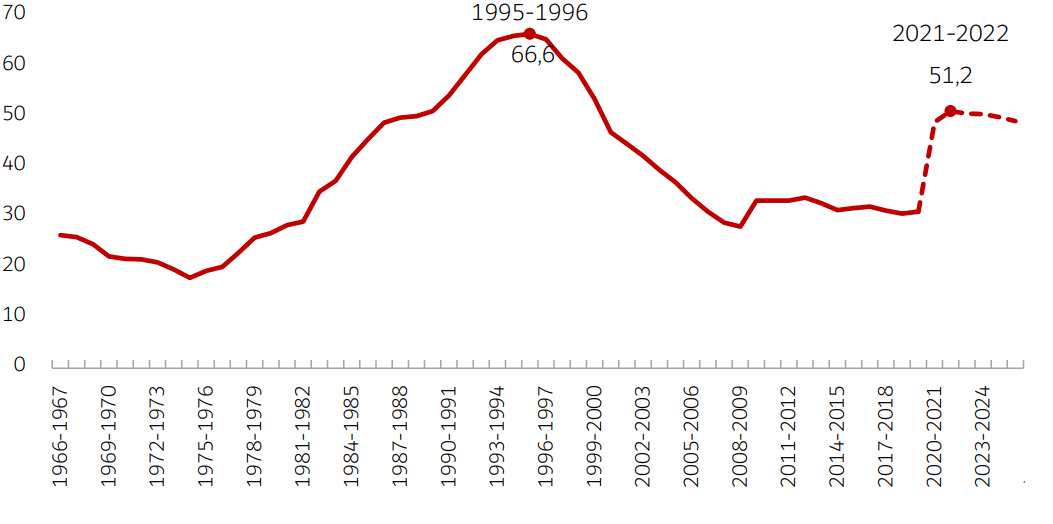

Lastly, the federal debt totalled $1,079 bn as at March 31, 2021, a 49.6% increase over the previous year. It is projected to stand at $1,411 bn as at March 31, 2026.

The debt-to-GDP ratio is anticipated to peak at 51.2% in 2021-2022, which is higher than at any point since the early 2000s. Nonetheless, this is lower than the previous peak of 66.6% in 1995-1996. The debt-to-GDP ratio is then expected to decline to 49.2% in 2025-2026.

Federal debt (% of GDP)

Source: Research Chair in Taxation and Public Finance at Université de Sherbrooke, Regard CFFP no. 2021-04, author: Luc Godbout, Chair.

Measures for individuals

- A Canada-wide child care system will be implemented. This is expected to reduce average child care costs by 50% in all provinces except Quebec by the end of 2022.

- An average child care cost of $10 per day is sought for all authorized child spaces by 2026.

- The government plans to inject $30 bn into the program over a five-year period, and $8.3 bn per year as of 2026.

- Compensation will no doubt be arranged for Quebec, which already has a child care program.

- Old Age Security benefits will be increased for people aged 75 or more:

- In August 2021, a lump sum of $500 will be paid to each OAS pensioner who will be 75 or older in June 2022.

- The maximum OAS benefit will increase by 10% in July 2022, for an average increase of $766 in the first year.

- Certain assistance programs will be extended and/or made more generous:

- The Canada Economic Recovery Benefit (CERB) for people not eligible for Employment Insurance is extended by 12 weeks (for a maximum of 50 weeks) until September 2021. The benefit for the last eight weeks will be $300, rather than the current amount of $500.

- The eligibility rules for Employment Insurance (EI) will be standardized and simplified, and the maximum duration of the EI sickness benefit will increase from 15 to 26 weeks.

- The eligibility criteria for the Canada Workers Benefit, intended for lower-income workers, will be broadened.

- There will be a new sales tax on luxury items:

- It will apply to new cars and private aircraft priced worth more than $100,000, and to pleasure boats worth more than $250,000.

- The tax will be calculated at the lesser of 10% of the total price, or 20% of the value exceeding $100,000 or $250,000.

- The government is introducing a new tax on the unproductive use of domestic housing by foreign non-resident owners.

- This tax will begin to apply on January 1, 2022.

- A 1% tax will be imposed on the value of non-resident, non-Canadian-owned residential real estate that is considered vacant or underused.

- All owners other than Canadian citizens or permanent residents will be required to file a declaration as to the use of their property.

- Residential owners will be eligible for an interest-free loan program enabling them to borrow up to $40,000 for retrofits aimed at improving energy efficiency.

- The waiver of interest accrual on federal student loans will be extended until March 31, 2023.

Measures for businesses

- The Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy (CEWS) will be extended until September 25, 2021, with a gradual decrease in the base and top-up rates beginning July 4.

- The rent subsidy will be extended unchanged until July 4. Thereafter, subsidy rates will gradually decline.

- A new hiring subsidy will cover up to 50% of the salary paid by eligible employers from June 6 to November 20, 2021. This subsidy is intended to offset part of the additional costs of reopening businesses. Employers will be able to choose whichever subsidy benefits them more: the CEWS or the new hiring subsidy.

- Businesses willing to invest as the crisis ends will be allowed to immediately expense $1.5 million per year over the next three years. Most investments other than real estate and goodwill will be eligible.

- The minimum wage for federally regulated businesses (banks, telecoms, trucking, etc.) will increase to $15 per hour.

- One dollar bn in aid is reserved for the sectors most affected by the pandemic and by lockdown measures, notably the tourism and hospitality industries as well as festivals and other events.

- The announced green recovery measures total $17.6 bn over five years:

- $5 bn, on top of the $3 bn announced last December, will be invested in reducing greenhouse gases (GHG) and reaching carbon neutrality by 2050.

- The target is now a 36% reduction in GHG by 2030, compared to 2005 emissions. The previous target was a 30% reduction.

- Income tax rates for businesses specializing in green technologies, such as wind turbine, solar panel, electric vehicle, battery, charging station and biofuel manufacturers, will be reduced by 50%. The reduction will apply from January 1, 2022 to January 1, 2029. The rates will then increase from 2029 to 2032 until they attain their previous levels.

- The government proposes to invest $3 bn in long-term care homes over a five-year period in order to improve services and ensure that the care and services provided by provinces meet national standards.

- An investment of $2.2 bn is proposed to strengthen the bio-manufacturing and life sciences sector and enable the country to manufacture its own vaccines.

- A $4 bn four-year package will help SMEs acquire new technologies that will enable them to go digital and enhance their efficiency and competitiveness.

- The government proposes to make an $18 bn investment in indigenous communities over a five-year period, $4.2 bn of which will be expended in 2021-2022, to build infrastructure and help the communities combat COVID-19.

Our analysis

The federal budget contains numerous measures which the government claims will enable the country to see its way out of the pandemic. These measures will have an economic impact, notably on growth, the bond yield curve, and long-term inflationary pressures.

Growth

The government’s message conveyed in the budget is that the proposed measures are needed to defeat COVID-19 and restart the economy. In the government’s opinion, now is not the time to think about debt and deficits. But is this the right approach for the country?

According to Minister of Finance Chrystia Freeland, it would be foolish not to take advantage of low interest rates by means to boost spending. This is encouraged by the Bank of Canada, which is anchoring rates at close to zero because it is not anticipating any significant increase in inflation for the moment. The emphasis on deficit spending rather than fiscal conservatism represents a shift from previous decades. This change in mindset, which is a positive factor for short-term growth, is happening worldwide.

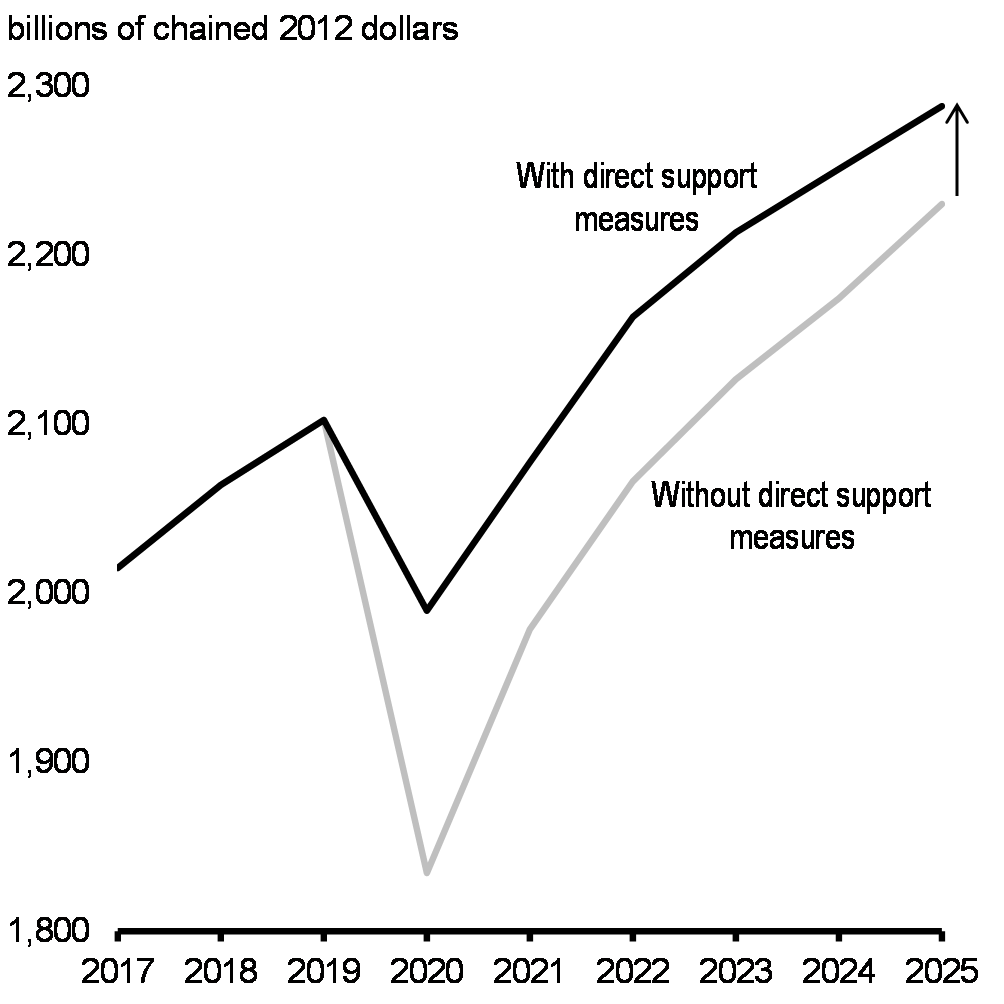

With this increase in spending, the government is mitigating the decrease in growth caused by the pandemic by stimulating consumption. According to the 2021 budget, this will support the GDP, which is expected to grow by 5.8% in 2021, 4.0% in 2022 and 2.1% in 2023.

Real GDP

Steepening of the bond yield curve

The government expects the deficit to fall back below the country’s nominal growth in 2022-2023. Thus, the debt-to-GDP ratio will peak in 2021-2022 before trending down over subsequent years. According to budget data, thanks to the multiplier effects due to the stronger GDP growth in the short term, debt-to-GDP levels are forecast to be roughly where they would have been without the stimulus measures by 2025.

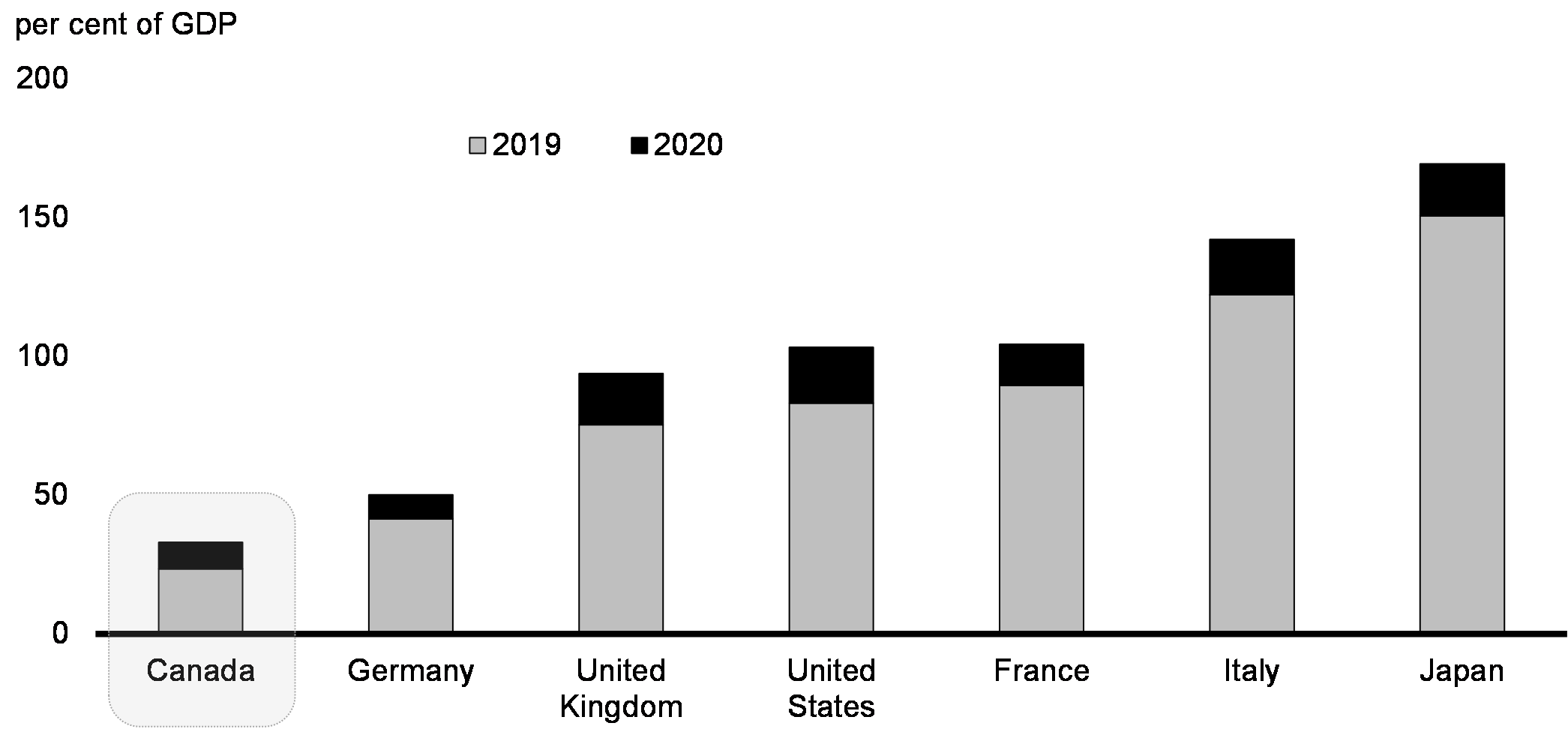

Canada’s net federal debt is lower than those of the other G7 countries, as shown in Chart 6. Furthermore, the S&P rating agency has already confirmed the country’s AAA rating following its assessment of the budget, while Moody’s reiterated its confidence in that rating back in February. This puts Canada in an enviable position.

General Gouvernment Net Debt, G7 Countries

Note: The general government definition includes the central, state, and local levels of government, as well as social security funds. For Canada, this includes the federal, provincial/territorial, and local government sectors, as well as the Canada Pension Plan and the Quebec Pension Plan.

Source: IMF, April 2021 Fiscal Monitor; Department of Finance Canada calculations.

Nonetheless, the projected deficits will need to be financed and absorbed by the market. The Bank of Canada, which was buying $4 bn in government bonds per week until April 2021, will now be buying only $3 bn per week, for an annual purchase of $156 bn. If this rate of purchase remains unchanged through 2022, the Bank of Canada would be purchasing the equivalent of 100% of new issuance in 2021 and 260% of new issuance in 2022. The Bank’s purchases are expected to lessen the upward pressure on interest rates caused by the increase in supply.

At the same time, the federal government plans to increase the average term to maturity of the bonds it issues: it will stand at close to nine years in 2021-2022, versus seven years in 2020-2021. Until now, the Bank of Canada has been buying bonds with a 7.5-year term as part of its quantitative easing program, and it has announced that it will not be increasing the term of its purchases to match the government’s new issuance strategy. There will therefore be a mismatch between the Bank’s purchases and the government’s new issuance; this will put some upward pressure on long-term bond yields (while the opposite will occur for short-term rates). The result should be a steepening of the bond yield curve.

Long-term inflationary pressures

Over the longer term, increased reliance on budget deficits supported by artificially low interest rates will have an inflationary impact. Several countries have implemented quantitative easing programs since the 2008 crisis, and although this supported the prices of purchased assets, it has had little impact on the real economy, and thus, on inflation.

In the current context of budget deficits, where money is going into the pockets of households that have a strong propensity to consume, the effect on inflation is expected to be more pronounced. Indeed, the resulting increase in demand for goods and services will put pressure on supply chains and force an increase in input prices. Over time, this effect will prove inflationary because businesses will seek to preserve their profit margins by increasing the cost of consumer goods.

A significant and lasting increase in inflation might take some time to materialize, but current interest rates do not take this situation into account. Nominal bond yields should normally reflect a country’s real GDP and inflation rate. The yield of Government of Canada 30‑year bonds currently stands at 2%. If the annual real GDP growth is 2% over the next 30 years, this means that the market-implied inflation expectation is 0%. Even if inflation merely matched the central bank’s 2% target for the next three decades, the fair value of 30‑year interest rates should therefore be 4%, quite a jump from current levels.

Conclusion

We believe that our portfolios are designed to achieve the best potential performance in light of the three dynamics discussed above. To take advantage of the positive development in the global economy that is primarily driven by the various national economic stimulus programs, we are reducing our allocation in bonds to a minimum and favouring equities within balanced mandates. Furthermore, our bond portfolio is invested in very short bonds (with an average term of two years) and has no exposure to bonds maturing in more than 10 years, while the average maturity of the benchmark is eight years. As the yield curve steepens and inflation pushes long-term yields higher, longer bonds will incur capital losses. Our strategy will help avoid such losses and ensure that capital is preserved.

Legal notes

The information contained herein is provided for informational purposes only, is subject to change and is not intended to provide, and should not be relied upon for, accounting, legal or tax advice or investment recommendations. Where the information contained in this document has been obtained or derived from third-party sources, the information is from sources believed to be reliable, but Letko, Brosseau & Associates Inc. has not independently verified such information. No representation or warranty is provided in relation to the accuracy, correctness, completeness or reliability of such information.

Concerned about your portfolio?

Subscribe to Letko Brosseau’s newsletter and other publications:

Functional|Fonctionnel Always active

Preferences

Statistics|Statistiques

Marketing|Marketing

|Nous utilisons des témoins de connexion (cookies) pour personnaliser nos contenus et votre expérience numérique. Leur usage nous est aussi utile à des fins de statistiques et de marketing. Cliquez sur les différentes catégories de cookies pour obtenir plus de détails sur chacune d’elles ou cliquez ici pour voir la liste complète.

Functional|Fonctionnel Always active

Preferences

Statistics|Statistiques

Marketing|Marketing

Start a conversation with one of our Directors, Investment Services, a Letko Brosseau Partner who is experienced at working with high net worth private clients.

Asset Alocation English

Canada - FR

Canada - FR U.S. - EN

U.S. - EN