Letko Brosseau

Veuillez sélectionner votre région et votre langue pour continuer :

Please select your region and language to continue:

We use cookies

Respecting your privacy is important to us. We use cookies to personalize our content and your digital experience. Their use is also useful to us for statistical and marketing purposes. Some cookies are collected with your consent. If you would like to know more about cookies, how to prevent their installation and change your browser settings, click here.

The 3 percent Rule

Although the roles pension funds play in the economy are multiple, the responsibility of pension fund managers is to maximize returns. Since 2000, the returns in Canada have been better than other markets but without currency risks. While consultants encourage pensioners to have only 3 per cent of their investments in Canada, as this represents Canada as 3 per cent of the world economy, this allocation neither helps the pension funds nor the country.

The 3 percent Rule

Canada represents 3 per cent of the world economy; therefore, 3 per cent of Canadian portfolios should be invested domestically.

This rule states that portfolios should be invested across countries in proportion to their size. Small countries should invest a little percentage of their already small savings in themselves while bigger countries invest a large percentage of their sizeable savings domestically.

Each country investing in themselves and others in proportion to their size theoretically leads to each country receiving their appropriate share of world savings. But according to game theory, this is unlikely and unstable. A country that would decide to invest a larger portion of its savings in its own economy, while everyone else continued to follow the rule, would gain an immediate advantage.

It is also clear that small countries would be very dependent on foreign investment to fulfill their needs.

Strictly applying the rule to Canada would lead to 3 per cent of all world portfolios, including Canadian ones, invested in Canada and would leave the country dependent on the good graces of the rest of the world to make up the missing 97 per cent.

This illustrates the fundamental flaws with the argument that countries should be investing in themselves in proportion to their size in the world economy. This concept only makes sense if a portfolio were investing world savings. However, most Canadian portfolios are investing Canadian savings.

Domestic versus Foreign Investment

Another difficulty with the 3 per cent fallacy is that it only looks at the problem from a portfolio perspective and does not consider the differential impact of domestic and foreign investment on the domestic economy.

From a portfolio perspective, Canadian pension funds are managed in accordance with sound financial principles weighting risks and returns of investment opportunities all over the world. There is little difference between a foreign and domestic investment.

Nonetheless, there is an added element to domestic investment that is absent in foreign investment: the impact the investment may have on the investor’s regular income.

Two simple cases.

In case 1 a Canadian invests $100 abroad. After one year they repatriate the $100 and $10 in profit. Their return is 10 per cent.

In case 2 a Canadian invests $100 in a machine that produces $210 of product in the year. The costs are $100 of salaries and $100 of wear on the machine, leaving $10 of profit. Their return is equally 10 per cent.

In case 1, Canada’s GDP rises by $10, the profit. In case 2, it increases by $210, the salaries, the machine, and the profit. This is the economic perspective.

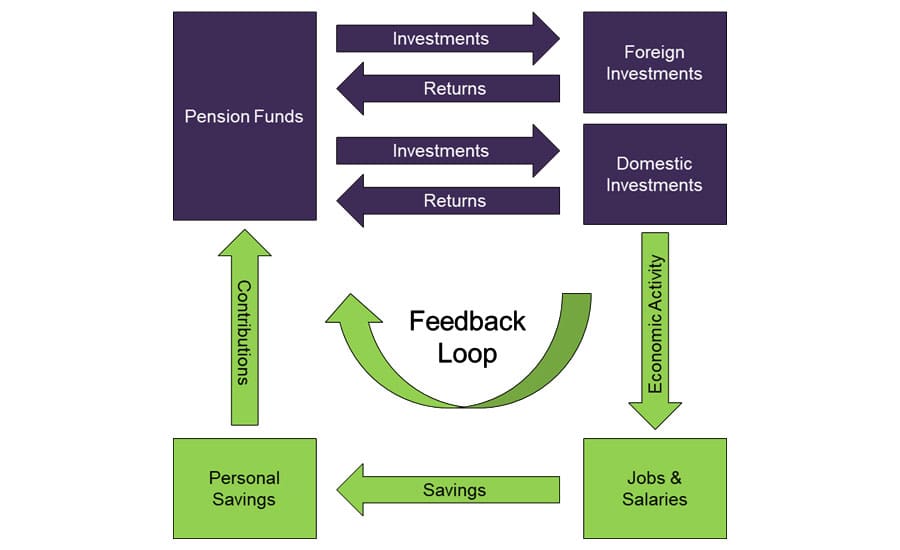

The Feedback Loop

From the Canadian investor’s point of view, the foreign investment produced an equal return but from a GDP perspective, the perspective of the Canadian investor’s income and ability to save, the domestic investment is by far the better one.

Benefits of Investment in Companies

Why do companies invest in their business? The answer is to survive and thrive, to exist. Investment is essential to succeed.

Business investment leads to:

- Increased revenues and profit,

- More efficient operations, increased productivity, reduced costs, increased margins,

- Greater economies of scale,

- Improved quality,

- Improved competitive position,

- Ability to attract and retain top talent,

- Enhanced reputation,

- Reduced risk,

- Increased innovation.

A business that does not invest in itself will soon lose out to its competitors and will fail.

Small companies need to invest just as much as larger ones, if not more because they often do not benefit from the same economies of scale. Some economists would argue that the battle is lost in advance and small companies will never be as efficient as their larger competitors. They would advise smaller companies would do better to conserve their capital, restrict their investments, and buy shares of their larger competitors. Luckily many have decided they want to take on the challenge and have figured out how to compensate for their disadvantages. Through investment, effort, and innovation, they have survived, grown, and become large enterprises.

A company’s principal source of funding is its own profits and cash flow. A considerable portion of its savings needs to be plowed back into the business to grow.

Benefits of Investment in Countries

Everything that has been said about companies can be applied to countries. A country needs to invest to survive and thrive otherwise they will fall behind and ultimately fail.

Investment in the country leads to:

- Increased gross domestic product (GDP) and incomes,

- More efficient operations, increased productivity,

- Improved competitive position,

- Increased jobs and incomes,

- Ability to attract and retain top talent,

- Reduced risk,

- Increased innovation.

The principal source of funding for country is the savings of its own citizens and businesses. Smaller countries generate less savings than larger countries. They have the same investment requirements as their larger counterparts, if not more.

Pension Funds

Pension funds in Canada represent approximately 37 per cent of institutional financial savings and about 30 per cent of household savings. They are just as large as the banks and 50 per cent larger than insurance companies. As a group, they invest approximately 33 per cent in Canada and 67 per cent elsewhere.

Based on financial reports and other sources, we estimate that the eight largest funds (Maple 8) are investing 25 per cent of their assets in Canada, less than the overall average. The largest of them is investing 13 per cent in Canada.

If we exclude fixed income, which is principally invested in government debt, the Maple 8 ratio falls to 15 per cent. This means that 85 per cent of their public and private equities, real-estate, and infrastructure investments put together are not Canadian but foreign. This high level of foreign investment is not limited to public equities.

Admittedly, pension funds are not strictly following the 3 per cent rule, but this still leaves Canada out 85 per cent.

Possible formula if we must

Let us assume each country allocates in priority some portion of its saving to its domestic economy (the “Domestic Allocation Bias”). What is left over, 100 % – Domestic Allocation Bias, is allocated to all countries, including the domestic country, in proportion to the size of their economy (the “Country Size”).

This can be expressed as a series of formulas:

Domestic Country Allocation = Domestic Allocation Bias

+ Domestic Country Size * (100 % – Domestic Allocation Bias)

Foreign Country Allocation = Foreign Country Size * (100 % – Domestic Allocation Bias)

Foreign Dependency = 100 % – Domestic Country Allocation

We see that if the Domestic Allocation Bias is 0 %, meaning there is no preferential allocation to the domestic economy, the Domestic Country Allocation is equal to the Domestic Country Size [= 0 % + Domestic Country Size * (100 % – 0 %)]. In Canada’s case, the Domestic Country Allocation would be 3 % and the Foreign Dependency would be 97 %.

If the Domestic Allocation Bias is 100 %, then all domestic savings get directed towards the domestic economy [Domestic Country Allocation = 100 % + Domestic Country Size * (100 % – 100 %) = 100 %]. The Country Size becomes irrelevant and there is no Foreign Dependency.

These are two extreme cases.

From the formulas we can estimate what the Domestic Allocation Bias is for different countries.

American investors allocate approximately 77 % to the US. Using the above formula for the US with a country size of around 55 %, its approximate average weight in the MSCI index over the last 30 years, gives us a Domestic Allocation Bias of 49 % [77 % = 49 % + 55 % * (100 % – 49 %)].

A peer group of large funds around the world[1] allocates 52 % to their domestic economies. Using the formula again for the peer group with an average country size of 5 % also gives a Domestic Allocation Bias of 49 % [52 % = 49 % + 5 % (100 % – 49 %)].

Using the same 49 % Domestic Bias Allocation for Canada, the formula would give a comparable Domestic Country Allocation of 51 % [= 49 % + 3 % * (100 % – 49 %)]. This percentage is far from the 33 % average for all pension funds in Canada, further from the 25 % of the eight largest funds, and very distant from the 13 % of the largest fund.

Conclusion

Investment opportunities exist all around the World, and the ones outside Canada can have a role to play. However, investments made in Canada not only impact pension portfolios, but also have an influence on Canada’s economy, generating jobs, improving incomes, and increasing contributions to retirement plans. Less investment in Canadian businesses increases their cost of capital, discounts their value, reduces their ability to grow, and makes the country less attractive.

This cannot be addressed through portfolio analysis. Only government regulations can deal with the problem from an economic perspective.

Canadian pension fund managers must maximize returns, and we reject the premise that investing in Canada will hinder their ability to do so, inevitably making them suffer. Not only is the premise contrary to historical fact, it also does not recognize all Canada’s advantages, its human and material resources, as well as its stable, equitable governmental and judicial system.

It is not wise to accept a system that siphons off Canada’s principal pool of long term, risk tolerable savings. There is a difference between foreign and domestic investments. Canadians benefit from foreign investments principally through their returns, but domestic investments produce returns and trigger a feedback loop into the economy that creates job, increases incomes and ultimately contributions. This feedback loop cannot be ignored. Companies and countries that do not invest in themselves risk falling behind and failing. Countries that do not invest in their own also fall behind.

Canada is rich in opportunity. It needs people that believe in its future and do not walk away.

[1] the top 100 state-owned funds reported by Global SWF

Where the information contained in this presentation has been obtained or derived from third-party sources, the information is from sources believed to be reliable, but the firm has not independently verified such information. No representation or warranty is provided in relation to the accuracy, correctness, completeness or reliability of such information. Any opinions or estimates contained herein constitute our judgment as of this date and are subject to change without notice.

This document may contain certain forward-looking statements which reflect our current expectations or forecasts of future events concerning the economy, market changes and trends. Forward-looking statements are inherently subject to, among other things, risks, uncertainties and assumptions regarding currencies, economic growth, current and expected conditions, and other factors that are believed to be appropriate in the circumstances which could cause actual events, results, performance or prospects to differ materially from those expressed in, or implied by, these forward-looking statements. Readers are cautioned not to place undue reliance on these forward-looking statements.

Concerned about your portfolio?

Subscribe to Letko Brosseau’s newsletter and other publications:

Functional|Fonctionnel Always active

Preferences

Statistics|Statistiques

Marketing|Marketing

|Nous utilisons des témoins de connexion (cookies) pour personnaliser nos contenus et votre expérience numérique. Leur usage nous est aussi utile à des fins de statistiques et de marketing. Cliquez sur les différentes catégories de cookies pour obtenir plus de détails sur chacune d’elles ou cliquez ici pour voir la liste complète.

Functional|Fonctionnel Always active

Preferences

Statistics|Statistiques

Marketing|Marketing

Start a conversation with one of our Directors, Investment Services, a Letko Brosseau Partner who is experienced at working with high net worth private clients.

Asset Alocation English

Canada - FR

Canada - FR U.S. - EN

U.S. - EN