Letko Brosseau

Veuillez sélectionner votre région et votre langue pour continuer :

Please select your region and language to continue:

We use cookies

Respecting your privacy is important to us. We use cookies to personalize our content and your digital experience. Their use is also useful to us for statistical and marketing purposes. Some cookies are collected with your consent. If you would like to know more about cookies, how to prevent their installation and change your browser settings, click here.

The climate is changing.

Electric vehicles are coming.

Should we still invest in oil?

March 24, 2021

Investing in oil companies at a time when climate change is accelerating and the uptake of electric vehicles (EVs) is increasing raises two important questions. Do such investments still make sense financially? More importantly, are they ethical? These are the issues this report strives to address.

The EV market is flourishing

The COVID pandemic brought many industries to their knees in 2020, but not that of EVs. While global car sales were down 15% y/y overall, EV sales were up an impressive 50%, ripping market share away from the internal combustion engine (ICE) segment. They made up 3.6% of all the world’s new car sales, compared to 2.4% in 2019.

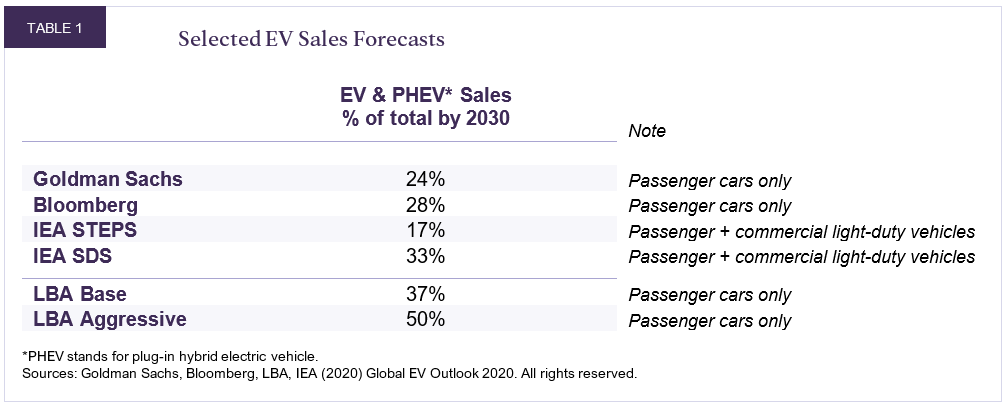

Along with the impressive sales numbers has come a build-up of massive expectations, thanks to continued technological advancements and the arrival of bold actions by policymakers. Many car companies have thus set aggressive EV sales goals to fulfill over the next decade and beyond. Most notably, GM recently stated the ambition to sell only electric vehicles by the year 2035. Industry observers have responded by upping their sales: Goldman Sachs, for example, now predicts that 24% of new passenger car sales will be electric by 2030 versus about 20% previously, and Bloomberg expects that 28% of new passenger car sales will be electric by 2030. In its Current Policies Scenario (STEPS), the International Energy Agency (IEA) now assumes 17% of new light-duty vehicles will be electric by 2030, up from 15% previously, while its more aggressive Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS) assumes 33% of new sales will be electric by then estimates (Table 1).

By our calculations, if car companies and governments achieve their current targets, 37% of new passenger car sales will be electric by 2030, compared with 20% based on last year’s targets. While it remains to be seen whether these goals can be met, it is hard not to conclude that the probability of a more rapid EV penetration scenario has increased.

An aggressive EV uptake scenario must therefore be considered

Given the above, risks to the oil market are clearly increasing. If one is long oil equities, one must contemplate the evolution of oil prices under a rapid EV uptake scenario—regardless of its likelihood.

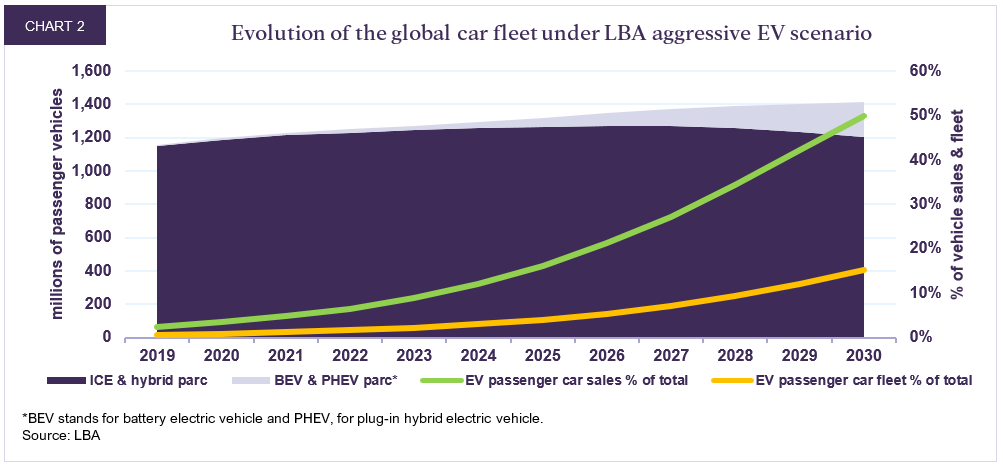

We do just that by considering a particularly aggressive EV scenario—one in which EV sales rise rapidly to reach 50% of total passenger vehicle sales by the year 2030. We ask what the impact is on the oil market, and whether investing in oil still makes sense, both financially and morally.

In the end, we find it difficult to escape the counterintuitive conclusion that oil demand will likely still be higher in 2030 than the pre-pandemic all-time high of 100 million barrels per day (Mb/d) reached in 2019.

Why is the market so sticky? The slow turnover of the passenger vehicle fleet is one oft-cited reason (Chart 2). And this is true, but to really understand the market’s stickiness, it’s important to look beyond passenger vehicles to the remaining roughly three quarters of oil demand that is not affected by the rapid adoption of passenger EVs. Peering under the hood of this surprisingly complicated market lays bare the lack of ready substitutes for the majority of products and processes that oil is used for.

Simply put, we find it highly unlikely that the oil market will go away in the next ten years—even if EVs rise to conquer the car market by the end of the decade.

Be that as it may, talk of the oil market’s resilience also misses a crucial point: climate change forces serious ethical questions around investing in the space at all. We address this in detail further below. At a high level, we find that ignoring the oil market as investors does little to alter the fact of climate change, while engaging with oil companies allows us to remind the industry of its environmental obligations.

Let’s first explore the long-term effects on oil demand from a rise in EVs.

What is the impact on oil demand of a 50% EV market penetration?

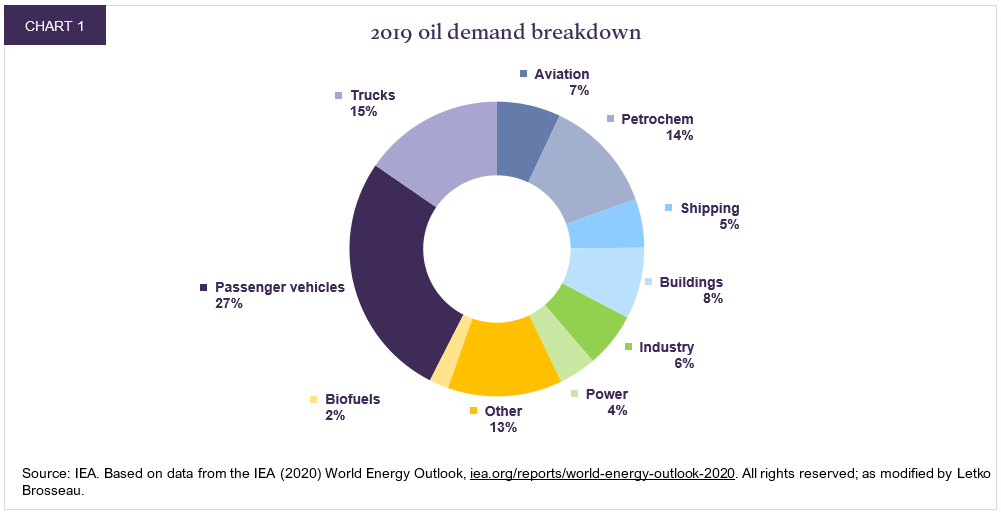

The roughly 1.18 billion ICE passenger vehicles on the road today made up 27.1 Mb/d, or 27%, of oil demand in 2019. They are by far the most important sub-segment of the world’s largest commodities market (Chart 1).

What happens to this 27.1 Mb/d volume under the aggressive EV uptake scenario? By our calculations, oil demand from this segment would only fall by about 14%, to 23.3 Mb/d. Even though EV sales thrive under this scenario, the size of the ICE fleet would still be comparable in 10 years to today, rising slightly to 1.20 billion cars by 2030. All else equal, a similar number of ICE vehicles on the road implies similar oil consumption. But after factoring in 2.0% assumed annual fuel efficiency gains, and assuming that driving patterns remain the same, we are left with a 3.8 Mb/d, or 14%, decline.

Now the question is whether the remainder of the oil market can make up for this 3.8 Mb/d deficit.

What about the rest of the oil market?

Trucking

At 15.4 Mb/d, trucking is the second-largest component of oil demand after passenger vehicles. Historically, road freight activity has increased at roughly the rate of GDP growth, and activity levels should continue to see robust gains, especially in emerging markets. Historical trucking fuel efficiency gains have been around 1% per annum, suggesting ample room for road freight fuel demand growth should GDP growth average 2 to 3%.

That said, oil demand growth from trucking could be tested as the potential for electric freight vehicles grows, with companies such as Amazon announcing initiatives to electrify their fleets. However, it is important to note that while heavy-duty trucks[1] (everything from 18-wheelers to garbage trucks) make up just 30% of trucks on the road and 6% of all vehicles, they consume around 80% of trucking fuel and 30% of all transportation fuels. This is due to both far worse fuel economy and far higher utilization: the average 18-wheeler can easily rack up 100,000 km in a year on four times worse fuel economy than a light commercial vehicle. Moreover, the light freight category is far easier to electrify via batteries or fuel cells than the heavy freight category, given that smaller vehicles have lower power needs and thus pose less of a technological hurdle.

And so, even as electrification breaks into the light commercial trucking segment, the 80% of the remaining market by way of oil demand will likely be much more resistant to substitution. And as emerging markets build up a highway infrastructure that facilitates more long-haul transportation, it is this oil-intensive heavy-duty segment that we think is especially primed for growth.

As a result, absent a far more rapid pace of development and deployment of battery- and fuel cell-powered electric heavy-duty trucks, we believe it is likely oil demand from trucking will continue to grow this decade.

Assuming that road freight activity grows in line with GDP, that efficiency gains average higher than historically and that electrification displaces the equivalent of 20% of light commercial trucks’ oil consumption by 2030, oil demand from trucking would grow to 17 Mb/d compared to 15.4 Mb/d in 2019.

Petrochemicals

Petrochemicals represent around 13% of the pre-pandemic oil market. The segment has recently grown faster than GDP, and there is near-consensus from industry observers that it will be the number one driver of oil demand growth for the foreseeable future. This is especially due to increased plastics penetration in emerging markets. India’s per capita consumption, for example, stood at less than 10% that of Canada in 2015. Other essential products derived from petrochemicals, such as fertilizers and synthetic rubber, should continue to grow as well. While there are risks that stem from highly sensible policies such as plastic bans and recycling mandates, we believe that the potential impact on oil demand will be relatively muted. For instance, according to the IEA, the potential for further single-use plastic bans represents just 2% of total plastics consumption by weight; plastic forks and disposable cups may be ubiquitous in our daily lives, but their low density makes them just a sliver of total industry output.

Given the above, we assume that oil demand from petrochemicals will grow at a compound annual rate of 2% from the 2019 level of 12.5 Mb/d to reach 15.6 Mb/d by 2030.

Aviation

Until the pandemic brought this industry to its knees, demand for air travel had risen at a remarkable 5% annual clip since 2000. While the timing of a recovery is uncertain, we can hardly imagine a post-COVID-19 world where air travel does not eventually return to robust growth. Eighty percent of the world’s population has never taken a flight, according to Boeing[2], and as economic growth elevates the wealth of millions in emerging markets, many will be taking their first.

But at least over the next decade and probably well beyond, it will be difficult to send these new travellers on their way without airplanes consuming significantly more oil than today. Aircraft electrification is far more challenging than for passenger cars due to much greater power needs. There are several prototypes and non-commercial projects out there, but no alternative is close to materially eating into oil’s stranglehold on the sector this decade. As a result, more planes in the sky necessarily translates into more jet fuel consumption.

Assuming that aviation activity grows at 3.5% between 2023 and 2030 and that aircraft achieve 2% per annum efficiency gains (the recent annual average is 1.4% per available seat kilometre), oil demand from aviation would increase from 7.0 Mb/d in 2019 to 7.8 Mb/d by 2030.

Shipping

Huge vessels that require lots of power are often used in shipping. As with airplanes, this makes electrification more difficult. Instead of EVs, other alternative fuel sources such as liquefied natural gas (LNG), methanol, biofuels and ammonia are being considered or already adopted. All have various barriers to overcome, ranging from infrastructure to technological maturity to energy density, but progress on many fronts is being made. Moreover, the International Maritime Organization’s fairly aggressive goal of a 40% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 relative to 2008 levels is helping to prod shipowners to consider alternatives. Of those mentioned above, LNG is by far the frontrunner. But new LNG vessels are more expensive, while emissions are only up to 15% lower than traditional shipping fuels on a full life-cycle basis (though harmful emissions such as sulphur and particulate matter are essentially eliminated). Most important, like the passenger vehicle car park, it would take years of strong new build sales of LNG or other alternative fuel vessels to materially alter the makeup of the fleet and reduce demand for oil.

Thus, as long as we have a larger global economy with more trade between nations, here is yet another component of oil demand that it is hard not to imagine larger in 10 years than today.

Assuming that shipping activity grows in line with GDP, that efficiency gains are in line with historical rates, and that around 5% of the shipping fleet runs on alternatives other than biofuels by 2030, oil demand from shipping would grow to 5.9 Mb/d by 2030 from 5.3 Mb/d in 2019.

Buildings, industry, power and other uses

The remaining roughly 30% of the oil market is lesser-known but equally important to consider.

At 7.8 Mb/d in 2019, buildings consume more oil than airplanes, primarily for space heating in homes and places of business. Rural areas in particular will likely continue to rely on heating oil. There will, however, be downward pressure over time on demand from this segment as most new homes use natural gas or electricity, though this should be partially offset by increased use of liquid petroleum gases (such as propane) for home cooking in emerging markets. The IEA estimates that oil demand from buildings will decline to 7.1 Mb/d by 2030.

Industry, at 6.0 Mb/d, has a plethora of different uses for oil, especially diesel, from running tractors and other machines to powering boilers. Oil is expected to slowly lose share to natural gas and electricity for some applications, but this should be mostly outweighed by increasing economic activity. The IEA estimates that oil demand from industry will decline to 5.8 Mb/d by 2030.

Power generation consumed 4.1 Mb/d of oil in 2019. Although a small piece of the pie, this may be the lowest hanging fruit for the oil market in the fight against climate change as substitutes are already available. In the Middle East for instance, home to 40% of the world’s oil power generation, oil-to-gas switching is expected to gain momentum as countries like Saudi Arabia use domestic natural gas reserves to free up crude oil for export instead. The IEA estimates that oil demand from power generation will decline to 2.8 Mb/d by 2030.

Finally, there is about 12.6 Mb/d left over for a hodgepodge of mostly difficult to replace products, from bitumen used in making asphalt for roads, to lubricants, waxes and other products. Generally speaking, consumption should increase with economic activity. We estimate that oil demand from these end uses will grow to 13.1 Mb/d in 2030.

The inescapable conclusion: oil will be very difficult to replace this decade

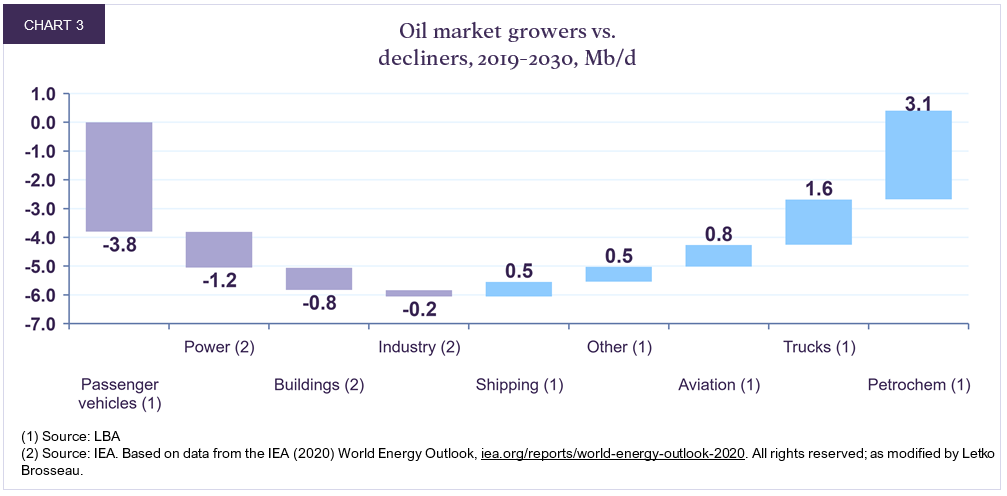

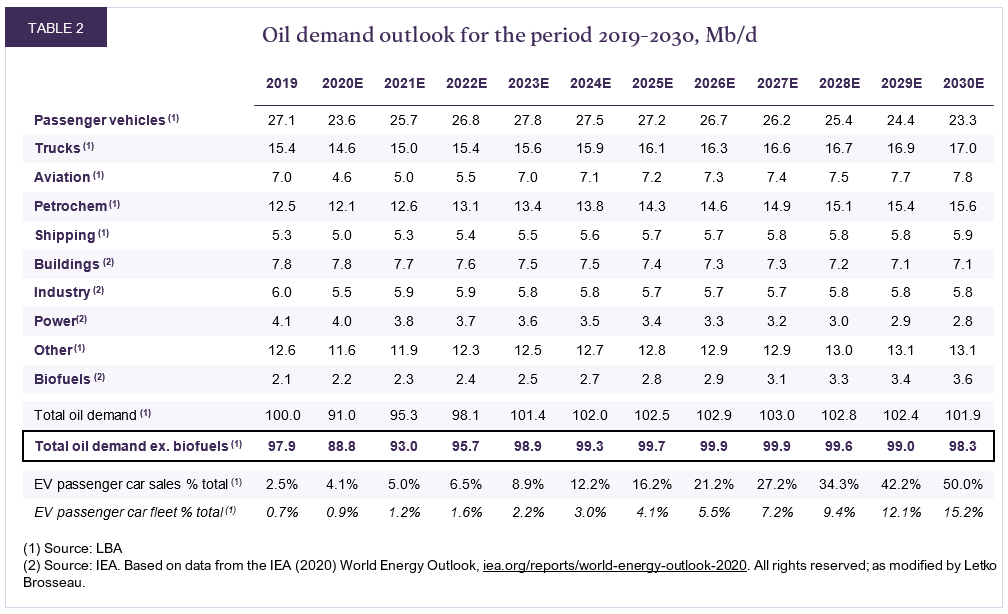

Putting it all together, under the above high EV adoption scenario over the course of the next decade, oil demand gains from growing segments (trucking, petrochemicals, air travel, shipping and other) of 6.5 Mb/d slightly offsets the shortfall from declining segments (passenger vehicles, buildings, industry, and power) of 6.1 Mb/d (Chart 3). Thus, after taking into account increased biofuels penetration, this analysis pegs crude oil demand at 98.3 Mb/d in 2030 versus 97.9 Mb/d in 2019, and shows demand peaking at just under 100 Mb/d in 2027 (Table 2). Crucially, this is the case even under the aggressive assumption that electric vehicles blow past many current estimates to reach a remarkable 50% of the car market by 2030.

As mentioned, one of the reasons for the counterintuitive result is that it takes years for the passenger vehicle fleet to turn over and fully electrify: in this scenario, we estimate that only 15% of cars on the road will be electric by 2030 even though sales reach 50%.

But a more meaningful takeaway comes from sifting through the individual line items of the market: oil simply lacks readily scalable substitutes. The above analysis makes clear that in order to argue oil’s decline this decade, significant portions of the heavy-duty trucking, airplane or maritime fleets would have to run on alternative technologies that do not yet exist, or are nascent and unlikely to scale fast enough. Or, for instance, that plastic consumption will fail to sharply penetrate emerging markets despite rising living standards. These hypotheses are hard to defend.

Therefore, we think it is difficult to escape the reality that oil demand will continue to increase for most of this decade.

What are the implications of the oil market’s resilience…

… for climate change?

Perhaps the main implication of the above analysis is that the oil market is unlikely to carry its weight in the fight against climate change, at least over the next decade. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), to achieve emission reduction goals that would limit climate change to a 1.5 degree warming scenario, primary energy consumption from oil will have to decrease by 8%[3] versus the 2010 level by 2030. That’s a crude oil market of around 80 Mb/d, implying a massive 20% decline over the next decade. In this light, our analysis of the oil market’s stickiness is extraordinarily sobering if also disheartening. But confronting this reality at least allows us to ponder what to do about it. On the one hand, it underscores the desperate need to decarbonize the vehicle fleet as fast as possible. On the other, it informs us that the more likely path to limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees is for the renewable power sector to take on an even greater role in displacing emissions from coal and natural gas (but especially the former). It also means that carbon capture and sequestration may be even more important than currently envisioned.

But this begs another question. With the situation this grim, how does one justify investing in oil at all? Shouldn’t we forego supporting an industry that the world is already having trouble shaking, for which the consequences of not doing so could be dire? We address this crucial question further below.

… for oil prices?

Conceptually, believing that demand is at least unlikely to decline over the next 10 years goes a long way towards a constructive price outlook. But where prices ultimately settle also depends on supply.

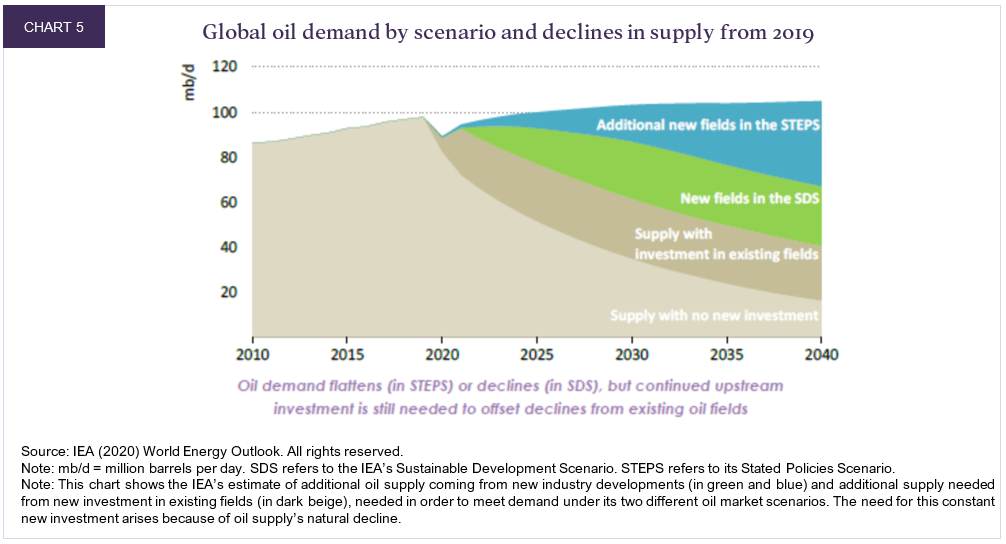

The relentless treadmill of the oil market’s 4–5% annual decline rate implies that companies need to develop 20–25 Mb/d of additional new capacity over a five-year period just to keep supply flat at 100 Mb/d (Chart 5). Prior to the pandemic, we were already firmly bullish on the outlook for the supply/demand balance, mostly because our work showed that after five years of underinvestment, certain parts of the oil market would enter steeper declines, while at the same time, US oil producers’ productivity and access to capital were deteriorating. And it appeared there was truth to this: in the early days of 2020, the price of Brent oil reached $70 before the pandemic took hold.

Now, after a year in which oil companies slashed capital spending to the bone in a desperate attempt to preserve liquidity, and in which some producers such as BP and Shell announced plans to shift more spending to other endeavours and accept that their oil production will decline—indicative of a permanent flight of capital from the industry—we are even more doubtful that supply can easily keep pace with demand. In addition, seeing their stock prices pummelled has forced many large public oil companies around the world to promise a strict diet of capital discipline, meaning less cash for drilling new wells, and more for shareholder returns.

We’ve estimated global oil production over the next five years. Assuming that 1) US production rebounds strongly to exceed its record 2019 level by 1 Mb/d, that 2) OPEC rebounds to full 2019 output and that 3) Iran returns to the market, we believe that oil supply in 2025, at around 102-103 Mb/d, would still only just equal demand under our high EV uptake scenario. If demand is higher than this, we do not believe the oil market will have many low-cost levers to quickly bring on new supply.

As demand is expected to continue to grow and supply could remain constrained, we believe that the market will tighten significantly once the effects of the pandemic have receded. We think that the marginal cost needed to bring on additional supply to meet demand is equivalent to at least $60 WTI; we assume WTI oil will average $60 this decade, even though we see substantial upside potential, especially over the next several years.

… for oil equities?

Many oil companies are tremendously profitable at a $60 oil price. On average, we estimate that our portfolio companies would generate a free cash flow yield of 25% and trade at just 2.9x cash flow in 2022 at $60 oil, based on current share prices. And given renewed industry focus on shareholder returns as opposed to reinvesting in the business, we think that more of this excess cash than ever will be used for dividends and share buybacks. Our energy companies currently yield a healthy 2.5% on average.

As ethical issues pushing investors away from the oil market are unlikely to dissipate, we do not expect oil stocks to again trade in-line with historical valuation multiples. However, we think valuations such as those above still leave ample room for upside. By 2024, we expect an average annual appreciation of 25% for our energy holdings.

The elephant in the room

Above, we laid out the case for why oil will not soon go away and why this makes for a compelling investment thesis in terms of dollars and cents.

But the discussion so far is oblivious to the urgency of the climate problem facing us, and whether we as investors have a role to play.

Herein lies the dilemma:

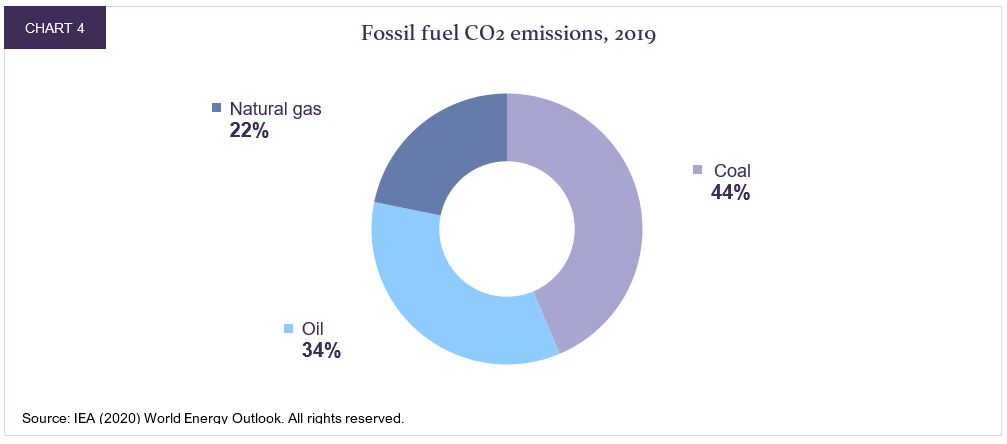

On the one hand is the reality that climate change is an existential threat that risks our livelihoods and those of future generations. The science has been clear for years and we need not revisit it here. Oil, a fossil fuel that accounts for 34%[4] of global CO2 emissions annually, is one of the three primary culprits, and reducing our consumption is key to limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees.

But on the other hand is the reality that oil is so inextricably linked with our daily lives that it makes undoing our dependence extremely challenging anytime soon. One way to understand this is by looking at the different components of the oil market, as we have done. We see that only a few of the many uses of oil have readily scalable substitutes that are even close to displacing petroleum products. We simply cannot go about our daily lives without oil—at least not yet.

We are under no illusion: the two realities above are indeed irreconcilable. Continuing to consume oil helps fuel climate change, but stopping our consumption seems impossible.

So, as investors, what are we to do?

One option that continues to gain traction is to divest from fossil fuels altogether. Many decide out of personal preference not to participate in an industry with such a negative externality, and we respect that. But whether one invests or not, a truck in India will need to move freight, a computer keyboard made of plastic will be bought in China, and fertilizer will be used to grow crops somewhere in Brazil. Oil demand doesn’t care whether we invest in public oil equities or not, so divesting does little to alter the reality of climate change, while at the same time it ignores the reality of our everyday lives.

To be fair, there is a logical element to the divestment strategy: reducing investment in public equities increases the cost of capital for oil companies, driving up their cost of supply and thus the price of oil. Higher prices make oil less competitive with substitutes, thus facilitating the energy transition, or so the thinking goes.

And, in truth, we believe this probably would help marginally erode oil’s market share. But we also think that 1) the ultimate effect on oil demand may not materially help mitigate climate change, and 2) the unintended consequence is a tax on the world’s lower-income population. Lower income populations such as emerging market workforces spend a disproportionate amount of their earnings on energy. For many, commuting to work every day, heating their homes or buying cooking fuels is not discretionary spending but an every day fixed cost of living. We cannot think of a less equitable way of driving the energy transition than to force higher living expenses upon those who can least afford it. Purposely driving oil prices higher does just that.

For these reasons, we support an alternative option of engagement. Instead of turning our backs on the oil market and hoping it goes away, we seek to engage with the industry to understand what management teams are doing to minimize their impact on the climate. For instance, oil extraction and refining are energy-intensive processes; we estimate that they contribute about 8% of global CO2 emissions. It is a significant piece of the pie, but many oil companies are going to great lengths to reduce their own emissions. While this misses the point that the problem resides far more in what they produce rather than in the process, it is at least worth noting that these companies have made as much tangible progress, if not more, than firms in many other industries at addressing what they can actually control—their scope 1 and 2 emissions. Being owners of these companies allows us to maintain a voice at the table and to push them to prioritize such endeavours. Divesting would remove this ability.

Meanwhile, several of our portfolio energy companies are tackling the energy transition head-on. For instance, Shell and Total, two of the largest oil companies in the world, have also become two of the world’s large renewable energy investors. Suncor is investing in wind farms. ConocoPhillips, one of the largest US oil companies, has set a net zero emissions ambition by 2050 and joined an organization dedicated to lobbying for a national US carbon tax.

Would these green initiatives have materialized absent a shareholder base that actively engaged the companies? It’s difficult to know for sure, but at the very least it probably didn’t hurt. The planet needs many more such initiatives, and we will push for them on behalf of our clients—but we can only do so if we have a seat at the table.

Conclusion

About a year ago, the world’s largest money manager, Blackrock, made big news by announcing an environmental, social and governance (ESG) overhaul of its investment process. The asset manager put special emphasis on climate change, promising to begin divesting certain fossil fuel companies such as those producing thermal coal, and to scrutinize the environmental characteristics of its investments like never before. It intends to double its ESG exchange-traded funds over the next few years to 150. In his annual letter to chief executive officers, CEO Larry Fink argued that due to awareness of climate risks, “we are on the edge of a fundamental reshaping of finance.” We agree.

But beneath the headlines was an important yet overlooked acknowledgement: “the energy transition will still take decades” and “the technology does not yet exist to cost-effectively replace many of today’s essential uses of hydrocarbons. We need to be mindful of the economic, scientific, social and political realities of the energy transition. Governments and the private sector must work together to pursue a transition that is both fair and just—we cannot leave behind parts of society, or entire countries in developing markets, as we pursue the path to a low-carbon world.” (emphasis added)

In writing these words, he was staring down the same two irreconcilable realities that we are.

In our opinion, choosing not to invest in oil companies focuses solely on the reality of climate change, while ignoring that of our everyday lives. We, on the other hand, believe the best we can do for our clients and for the planet is to honestly recognize both sides of the coin. In doing so we can actually help influence the outcome.

We do, however, acknowledge that one day the rise of EVs may threaten the investment rationale for many oil companies. So it may not be a question of “if,” but “when” one winds down these investments. Here, we only submit that given (1) the resilience of oil demand this decade despite EV sales growth, (2) a sluggish post-pandemic rebound in oil supply, and (3) compelling company valuations, that day has not arrived.

Mr. Letko, a graduate of Columbia University (Executive MBA), University College Dublin (MA, Economics) and McGill University (BA, Economics), is a CFA® charterholder. Prior to joining the firm in 2018, he worked in equity research at Barclays in New York, where he covered the oil & gas industry from 2015 to 2018. Previously, he was an associate with the economic research team at Evercore ISI in New York (2013–2015).

Legal notes

[1] As defined by the IEA

[2] https://theicct.org/sites/default/files/publications/LNG%20as%20marine%20fuel%2C%20working%20paper-02_FINAL_20200416.pdf

[3] We have extrapolated the median decline of the four illustrative model pathways from an IPCC report (see Masson-Delmotte, et. al., 2018, “Global Warming of 1.5 °C. An IPCC Special Report,” in Summary for Policymakers, IPCC. Available at https://www.ipcc.ch/2018/10/08/summary-for-policymakers-of-ipcc-special-report-on-global-warming-of-1-5c-approved-by-governments/.).

[4] IEA, World Energy Outlook 2020 – Annex A

All dollar references in the text are US dollars unless otherwise indicated.

The information and opinions expressed herein are provided for informational purposes only, are subject to change and are not intended to provide, and should not be relied upon for, accounting, legal or tax advice or investment recommendations. Any companies mentioned herein are for illustrative purposes only and are not considered to be a recommendation to buy or sell. It should not be assumed that an investment in these companies was or would be profitable. Unless otherwise indicated, information included herein is presented as of the dates indicated. While the information presented herein is believed to be accurate at the time it is prepared, Letko, Brosseau & Associates Inc. cannot give any assurance that it is accurate, complete and current at all times.

Where the information contained in this presentation has been obtained or derived from third-party sources, the information is from sources believed to be reliable, but the firm has not independently verified such information. No representation or warranty is provided in relation to the accuracy, correctness, completeness or reliability of such information. Any opinions or estimates contained herein constitute our judgment as of this date and are subject to change without notice.

Past performance is not a guarantee of future returns. All investments pose the risk of loss and there is no guarantee that any of the benefits expressed herein will be achieved or realized.

The information provided herein does not constitute investment advice and it should not be relied on as such. It should not be considered a solicitation to buy or an offer to sell a security. It does not take into account any investor’s particular investment objectives, strategies, tax status or investment horizon. There is no representation or warranty as to the current accuracy of, nor liability for, decisions based on such information.

This presentation may contain certain forward-looking statements which reflect our current expectations or forecasts of future events concerning the economy, market changes and trends. Forward-looking statements are inherently subject to, among other things, risks, uncertainties and assumptions regarding currencies, economic growth, current and expected conditions, and other factors that are believed to be appropriate in the circumstances which could cause actual events, results, performance or prospects to differ materially from those expressed in, or implied by, these forward-looking statements. Readers are cautioned not to place undue reliance on these forward-looking statements.

Concerned about your portfolio?

Subscribe to Letko Brosseau’s newsletter and other publications:

Functional|Fonctionnel Always active

Preferences

Statistics|Statistiques

Marketing|Marketing

|Nous utilisons des témoins de connexion (cookies) pour personnaliser nos contenus et votre expérience numérique. Leur usage nous est aussi utile à des fins de statistiques et de marketing. Cliquez sur les différentes catégories de cookies pour obtenir plus de détails sur chacune d’elles ou cliquez ici pour voir la liste complète.

Functional|Fonctionnel Always active

Preferences

Statistics|Statistiques

Marketing|Marketing

Start a conversation with one of our Directors, Investment Services, a Letko Brosseau Partner who is experienced at working with high net worth private clients.

Asset Alocation English

Canada - FR

Canada - FR U.S. - EN

U.S. - EN